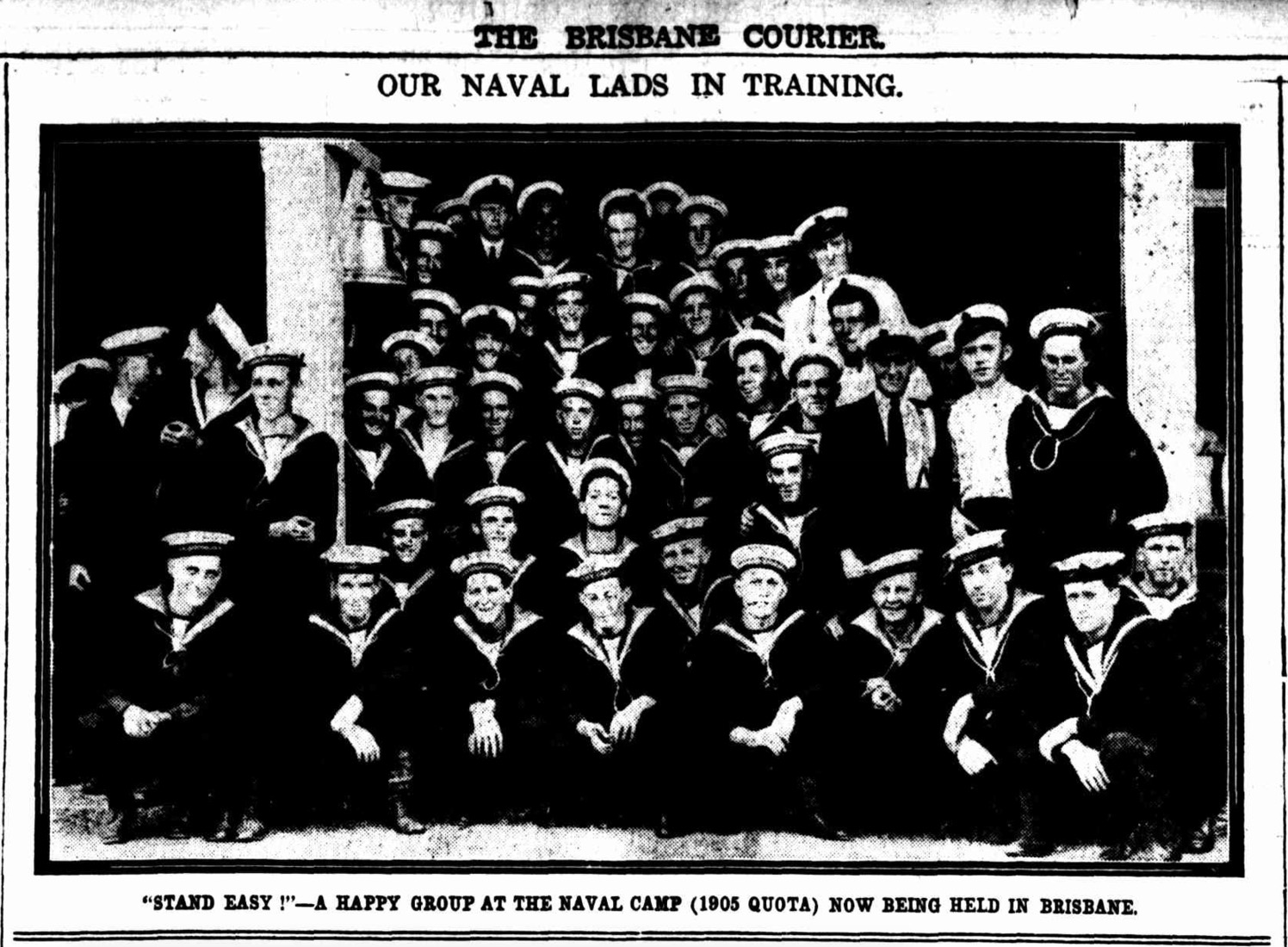

Training in 1904

ABOVE: No longer members of the Queensland Naval Brigade, but training at the Royal Australian Navy Stores at the foot of Kangaroo Point Cliffs were these trainee sailors of the gun crew of HMAS Warragul. They were pictured on page 13 of Brisbane’s “The Daily Mail” newspaper edition of 13 May 1926.

Naval Brigade: Annual Training Work.

Gunnery and Mine Practice.

WHILE the gunboats, Gayundah and Paluma, manned by 11 officers and 102 members of the Naval Brigade under Captain Creswell [ the future Sir William Rooke Creswell ] and Lieutenant Curtis [ George Arthur Hamilton Curtis ] are cruising in Moreton Bay, the balance of the brigadesmen mobilised at Brisbane for the annual continuous training are kept arduously in practice at the depot and on the river, Lieutenant Beresford [ Joseph Arthur Hamilton Beresford ] being in command, with Sub-Lieutenants Cameron [ Waverley Fletcher Cameron ], Neilson [ Trevor Neilson ], and Harrington [ Hubert Ernest Harrington ] as staff officers, and Gunners A.R. Knowles [ Alfred Richard Knowles ] and G.J. Jones [ George John Jones ] as instructors.

The muster also includes the Torpedo Corps, under Chief Gunner H.B. Miles [ Harry Benda Miles ] and Chief Petty Officer J. Thorne [ John Thorne ]; and the total number in camp was yesterday increased by fresh arrivals from the north to 71.

Staff Paymaster Pollock [ Edward Vincent Pollock ] is likewise present daily.

The round of duties yesterday included drill at field and machine guns, dotter practice, boat exercise, and the laying and exploding of mines.

The long range of double-storied buildings under the high cliff is thus once again the centre and base of warlike animation, from early ’till late.

The work goes on with orderliness, precision, and diligence, the men displaying aptitude and zeal, like true sons of the sea, who have to be soldiers and sailors both.

Obviously their training has to be very comprehensive, for has not the naval brigadesman to be fit for nearly all kinds of warfare?

He has to be not only a seaman but a gunner and an infantryman as well. If he is not expected to fight on horseback he may he relied on afield as well as afloat, and especially, in case of need, as a garrison artilleryman.

And so he was found at the depot yesterday handling the five-inch Armstrong gun on its Vavasseur Mounting, the 4.7 guns (most modern and effective of all), and field and machineguns, including Maxims and Nordenfeldts.

Their gunnery practice was educational in every necessary respect. Every weapon was manipulated and explained with scrupulous attention to detail.

Especially was explained the scientific principles on which guns were rifled, and the superiority of the rifling of the 4.7 weapons was pointed out.

The “dotter” practice was most interesting. It was quick firing at a target, and every hit was duly registered without the expenditure of any powder or shot.

The target was but a two-inch square of cardboard, within a few inches of the muzzle of the gun.

At every shot a dint was made on it by a striker, and an outer or a bullseye was recorded.

At other guns practice was made at objects on or across the river.

No record was taken in regard to this, but instructors were quick to show the men when they were firing at all wide of the mark.

The lower storey of the building is practically a formidable battery, but the guns are said to be easily removable, to boats or places which would confront, not Government House, but an enemy.

The upper floor is a labyrinth or passages and rooms containing sleeping spaces for blue jackets, a parlour-like room for the use of officers, stacks of rifles, and stores of infinite variety, from the useful sewing machines to the fish-like weapon of destruction, the torpedo.

Also significantly noticeable was an array of charged shells of various sizes.

It was learned or gleaned that for six weeks back the permanent staff had been very busily engaged loading shells, and that so much work has been done in this regard that there is now a full complement of ammunition for each gunboat, and also a large reserve supply.

The shells were differently coloured. Those charged with high explosives such as lyddite were painted yellow as a conspicuous colour of distinction. Others had red rings painted round their points to indicate the effectiveness of their condition.

In these the handy steam launch, Midge, and the rowing boats were important factors. In this section of the work, the Chief Petty Officer (J. Thorn) and the Chief Gunner (H.B. Miles) of the Torpedo Corps were actively directing and supervising.

It was dangerous work, and required much care as well as much knowledge.

There was what is called “creeping practice”. This appeared to be like trailing for mines or cables with loaded grapnels.

Then there was the laying of mines and countermining.

What was most spectacular was the explosion of mines constructed on a balancing principle. So long as these mines remain level they remain quiescent.

Immediately the balance is disturbed off they go and anything that may lie above them fares badly.

To practise effectively with this sort of business required ingenuity, so the balance to be disturbed was fixed on a buoy moored some 21 or 30 yards [ about 19 to 27 metres ] away from the miniature mines.

The Midge then rammed the buoy, and simultaneously a column of water was thrown 100 feet [ about 30 metres ] high, not very far back in her wake.

The officer commanding would cheerfully announce: “Now we are just passing over the mine; look out!” Then bang! and the waterspout.

There were also fish dead or stunned, showing their silvery breasts to the sun and a rush of a score of rowing boat to gather in the fishy harvest.

Alas, however, writing from a Brisbane point of view, the floating denizens of the river were only the catfish, which in times when the stream is over-fresh, annoy the angler, and which nevertheless are cultivated in other parts of the world as the most edible fish known.

There was, of course, an electric connection between the buoy and the mines. A number of explosions were fired off without accident.

The Marconi system has been relied upon for keeping up communication with the fleet.

No message was received by that method yesterday, but one was received by pigeon post. Some 120 pigeons are lofted at the stores for this purpose.

The message was from Captain Creswell and was to the effect that the weather was such that he had delayed erecting the Marconi pole, and that all was well.

— from page 3 of “The Telegraph” (Brisbane) of 2 April 1904.